Sociologist and Sugar Rush author Karen Throsby joins us to discuss why sugar became demonized despite a lot of actual uncertainty in the science, how anti-sugar sentiment is bound up with anti-fat bias, the different rhetoric around sugar that’s dominant in diet culture vs wellness culture, what the research really says about the supposed addictiveness of sugar, and lots more.

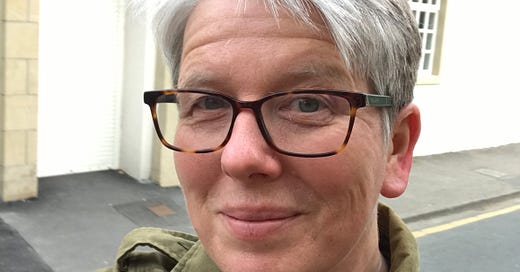

Karen Throsby is Professor of Gender Studies and the Head of the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Leeds. She has been researching issues of gender, technology, bodies and health for over 20 years, including work on reproductive technologies, weight loss surgery and endurance sport. She is the author of Immersion: Marathon Swimming, Identity and Embodiment (Manchester University Press, 2016), When IVF Fails: Feminism, Infertility and the Negotiation of Normality (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) and most recently, Sugar Rush: Science, Politics and the Demonisation of Fatness (Manchester University Press, 2023).

Resources and References

Karen’s latest book, Sugar Rush: Science, Politics and the Demonisation of Fatness

Christy’s latest book, The Wellness Trap: Break Free from Diet Culture, Disinformation, and Dubious Diagnoses and Find Your True Well-Being

Subscribe on Substack for bonus episodes and more

Christy’s online course, Intuitive Eating Fundamentals

Transcript

Disclaimer: The below transcription is primarily rendered by AI, so errors may have occurred. The original audio file is available above.

Christy Harrison: Welcome to Rethinking Wellness, a podcast exploring the diet culture, disinformation, dubious diagnoses, and disordered eating that are so pervasive in contemporary wellness culture--and how to avoid falling into these traps so that you can find your own true wellbeing. I'm your host Christy Harrison, and I'm a registered dietician, certified Intuitive Eating counselor, journalist, and author of the books Anti-Diet, which was published in 2019, and The Wellness Trap, which came out on April 25th and is now available wherever books are sold. You can learn more and order it now at christyharrison.com/thewellnesstrap.

Hey there. Welcome back to Rethinking Wellness. I'm Christy, and my guest today is sociologist Karen Throsby, who joins me to discuss why sugar became demonized despite a lot of actual uncertainty in the science, how anti-sugar sentiment is bound up with anti-fat bias, different rhetoric around sugar that’s dominant in diet culture versus wellness culture, what the research really says about the supposed addictiveness of sugar and lots more. This is a really great conversation. I can't wait to share it with you in just a moment, but before I do, I just have a few quick announcements. First one being that this podcast is brought to you by my newest book, tThe Wellness Trap: Break Free from Diet Culture, Disinformation, and Dubious Diagnoses and Find Your True Well-Being, which is now available wherever books are sold! The book is a great companion to this podcast because it explores the connections between diet culture and wellness culture; how the wellness space became overrun with scams, misinformation, and conspiracy theories; why many popular alternative-medicine diagnoses are misleading and harmful—and what we can do instead to create a society that promotes true well-being. Just go to christyharrison.com/thewellnesstrap to learn more and buy the book.

That’s christyharrison.com/thewellnesstrap or just pop into your favorite local bookstore and ask for it there. This podcast is made possible by my paid subscribers at rethinkingwellness.substack.com. Not only do paid subscriptions help support the show and allow me to keep making the best free content I possibly can because podcasting is not cheap. There's a lot that goes into it on the backend, a lot of work, a lot of time, and a lot of labor by other people as well. So paid subscriptions help support all that, and they also get you great perks like early access to every episode, bonus episodes including one that I did with Karen, this week's guest, biweekly bonus Q&As, subscriber-only comment threads where you can connect with other listeners, and lots more. Thanks so much to everyone who's become a paid subscriber so far, and if you want to join, you can go to rethinkingwellness.substack.com to sign up. That's rethinkingwellness.substack.com. Now, without any further ado, let's go to my conversation with Karen Throsby, thanks so much for being with us, Karen. I'm really excited to talk with you about your new book.

Karen Throsby: Thanks for inviting me.

Christy Harrison: Yeah, can you start off by telling us a bit about yourself and why you wanted to write a book about sugar?

Karen Throsby: Yeah, so I'm a professor of gender studies at the University of Leeds, and I've been working for quite some time now on issues around the body and things we do to change bodies in ways that try to bring them in line with social norms and expectations. So I've done work on reproductive technology, on surgical weight management, on endurance sport, and I was starting to look at food much more carefully as a way a means of changing our bodies in different ways, both in terms of performance and size and composition, and I was thinking about the sort of, so-called war and obesity and sort of noticed this shift that had happened in the 2010s where suddenly we were hearing just all about sugar. It was all about sugar, it was absolutely everywhere you were seeing sort of newspaper articles about sugar. Then all of these books were coming out, the sort of self-help books, the popular science books, and then we had certainly in the UK and also internationally as well, lots of policies around sugar reduction start coming up around 2014, 15, 16.

And it was clear to me from as a sociologist that something was happening there that sugar was now really supplanting dietary fat as the food enemy to fight in this sort of attack on fat bodies that has been quite long running. And so this sort of led me to then go to newspaper coverage and actually do a more systematic search to see if my kind of impression was actually correct. And I looked at newspaper coverage that had the word sugar in the headline for articles, substantial articles, so articles that were 500 words or more across nine newspapers in the uk. And what I found was from 2000 to 2020, it ticks along at a very low level until about 2012, and it's just a few articles a year, nothing much. And then it absolutely shoots up really noticeably up to 2016, which is when in the UK a sugar tax was announced and it was introduced in 2018. So we've got this kind of arc of just increased talk about sugar that's then matched with new policies with all the publication of these books. And so I decided to kind of look really closely at this and work out what's happening, what is the social life of sugar in this moment. So that was the driving question for the book that led to the research.

Christy Harrison: That's so interesting. Why do you think it is that there was such a marked uptick at that time?

Karen Throsby: Yeah, I mean I think this is quite UK specific in some ways. I think there are two reasons. The first is the, if you like that if we call it the war on obesity, this attack on obesity that we've had for a couple of decades, it's really losing steam around that time because it's basically beset by its own failures in terms of its own goals. It is a failure. So what it needs to do is constantly revive itself sort of in a new form. And one of the ways that it does that is that it finds a new enemy. And so in this case, there was a shift from fat to sugar and sugar became the new enemy that enabled all of those who were very heavily invested in an attack on obesity for all kinds of reasons to then get behind this act of blaming sugar.

So in some ways, I think it was just the flagging of the attack on obesity needs to be revivified every so often, and this was that moment. The second reason I think in the UK particularly was the introduction of austerity measures, which were following the 2008 financial crash. We sort of had a series of measures that sort of started coming in around 2010 under David Cameron's government. And in 2012 we had the Welfare Reform Act, which basically entrenched austerity measures. So for example, massive cuts to welfare provision, a lack of social support, and the idea that we are somehow all in this together, and yet it fell very unevenly onto the most disadvantaged. And what we get at this time is the language of David Cameron, the prime minister called Strivers and Skiver. So the strivers are kind of the good, honest, hardworking citizens who need a bit of help and are contributing and doing their bit.

And then we've got the skiver who are seen as the people who are kind of leaching off the benefits system aren't pulling their weight and the language of the attack on sugar. And I talk about this quite a lot in the book maps quite cleanly onto the language of austerity. You've got the people who care about their health enough who are seen as caring about their health enough to work hard at it, to give up sugar, to be as healthy as they can be. And then the people who were seen as sort of consuming in an uncontrolled way became the kind of skiver because these are the same people, the same language is used about people who were seen as consuming benefits in a uncontrolled way were seen as consuming sugar and then costing the state money. So I think it was those two things, the failure of the attack on obesity and the need to bring it back to life and this coincidence with austerity and this attack on those who were seen as not pulling their weight.

Christy Harrison: That's really interesting. Another thing in the book you mentioned is that some people ended up claiming that sugar was the root cause of so-called obesity all along and that we'd been misled by the war on fat. And I think that's really interesting context to this shift. You talk about people like Gary Tobbs and a couple of others that you explore their work and their Rhetoric around this. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Karen Throsby: Yes. So we saw a number of people step forward to become these authoritative voices on sugar. They write kind of popular science books where they sort of make a Scientific case or a case that claims to be Scientific that sugar was the problem all along. And that dietary guidelines, I don't know the eat well plate or those kinds of guidelines, the national guidelines were actually corrupted by the food industry as the most common argument, and in fact it was sugar all along. And they often look back to some very early advocates of anti-sugar, some people who attack sugar in the sort of seventies, but then this is revived as a kind of look now we can see finally there's a kind of truth to be told, and they're quite interesting because

They kind of gain status and authority from being people who speak against accepted truths. So they're the brave people who can speak out, who are going to tackle the food industry and tackle the corrupt government to access this truth about sugar. So they've got this sort of quite rebellious sort of refusal to be silenced, the undercurrent that goes throughout their work and through this, they claim a certain authority. Gary TAs, for example, is a science journalist. Robert Lustig is an endocrinologist, a pediatrician, and so they have different sources of authority through which they claim a new truth basically, or the uncovering of an old truth. And there's a kind of very strong certainty that underlines their narratives that sugar is the problem.

Christy Harrison: Yeah, no, it's so interesting that certainty you quote from these authors and point out those extreme levels of certainty. I recognize that type of certainty from social media too. I feel like it's just rampant these days and even a bit for my own first book and my own earlier writing and speaking where I think there's without any sort of intention behind it, but just the incentives of social media reward, that kind of clarity and lack of nuance and stripping things down to their most basic and not really giving a lot of caveats or nuance or looking at the other side of things. And I think for me personally, in many cases I might soften some of the language in my first book, even though I very much stand behind the ideas still the way I conveyed them I think could use a little more nuance. Same with a lot of early social media posts and stuff. But I think that kind of certainty and bluntness is not particularly good for the discourse, but it is really good for going viral.

Karen Throsby: Exactly. It's incredibly palatable is how I've been thinking about it. I find it interesting because a lot of the objection to sugar is about foods, the way that sugar makes foods hyper palatable. So just incredibly easy to eat and in many ways the message, the message is being communicated is also hyper palatable because the anti-sugar message, because it's very straightforward, like sugar is bad, that's the end. But also if you are marketing a book as in these cases, these anti-sugar books, then you have to have a simple and accessible message. And that gets then reproduced in social media, which is perfectly designed for blunt, simple messages. Those take home messages. What's quite interesting about these different authors is they also have to carve out a little space for themselves because quite a crowded field. So they each have to have something that's particular about their message, but also it has to be definitive. One might be talking about sugar in terms of addiction. One might be talking about it in terms of sugar as metabolically damaging. They also often disagree on what constitutes sugar. For some it'll be all carbohydrates, but others it'll be simply added sugar into food. For some it'll be fructose. And so they're kind of trying to find certainty and to carve out a space that makes their product and their identity unique and saleable, I think ultimately.

Christy Harrison: Right. Well, it's interesting too how there's just sort of this piling up of arguments against sugar and they might be contradictory or seemingly contradictory in some ways, but that they can sort of coexist and work together to create this wall of supposed certainty that sugar is bad.

Karen Throsby: And I kind of try and unpick this in the book. So I identified two sort of key strands of thought about sugar that are contradictory even though the message that sugar is bad is the kind of unifying message, and that's all we hear. But when you look at what kind of problem is sugar, they're different. So you get particularly mainstream government policies, et cetera, talk about sugar in terms of its emptiness. So it's empty, it's calories that bring no nutritional benefit, and that just is seen as a cause of fatness, which is then seen as a cause of the old very familiar stories about disease and so on. And so it's really presented in those terms. It's empty calories, and so it could be anything. The goal is to reduce calories in those narratives and sugar just happens to be something that is seen as high in calories to no other benefit.

And so there's that argument which is very focused just on reduction, eat less of it, which would mean fewer calories. So that very familiar narrative of calories in calories out that we see with the diet industry. But then there's this second position which is that sugar is in itself toxic, that yes, it's calorific, but that it is in itself toxic, that it does damage to the body, that it causes metabolic damage, that it damages organs, that it damages really every aspect of the body's systems. So they seem incompatible those two positions. But what I kind of realized was that they get held together with this idea that sugar is bad and it's done by firstly talking about fatness. And that fatness is treated as a known problem as a kind of, well, surely we can all agree that this is a terrible thing. And so that then provides a sign of unifying narrative that it doesn't kind of matter what kind of problem sugar is because it's so closely associated with fatness that we just have to stop it.

So that's one narrative. The second one is a narrative of addiction that sugar is seen as addictive and that kind of ramps up the hostility against sugar because it's then aligned with other legal and illegal drugs. So people often talk about it being cocaine, and of course because it's sort of white and powdery, it's very visually, it's very easy parallel to draw. So lots of talk about addiction, although if you actually scratch below the surface and ask what they mean by addiction, there's sort of many, many different versions of what that is. It's not at all clear what it means. And then the third thing is a kind of nostalgia. And so there's a nostalgia that runs through both the idea of sugar as empty calories and sugar as toxic. This idea that sometime in the past we didn't have this problem with sugar, but now the food supply has been contaminated.

So if we could just return to the past, it wouldn't really matter what kind of problem sugar is because it would be gone. And so the two places that we look is this kind of post-war 1950s imagined ideal of very low sugar, lots of physical activity, children running around all the time, not eating between meals. And then there's, which of course is a fantasy of the 1950s apart from anything else that relies on women doing an awful lot of domestic labor and home cooking. And then there's a second nostalgia, which is to a kind of paleolithic past very ill-defined, but of a time pre agricultural revolution when we all just sort of ate according to our appetites, hunted nibbled on berries for sweetness when they were in harvest and that we should somehow, if we stopped eating sugar, we could return to this idealized past. And so in these ways, in a sense, the different ways of understanding what kind of problem, sugar is cease to matter because there's a kind of overarching narrative, well, sugar is bad and we have to stop eating it.

Christy Harrison: I think that's so interesting, and I see those three different narratives about sugar cross-pollinating and showing up in so many different ways in wellness culture and diet-culture. I think the notion that sugar is just empty calories, you point out that that's sort of the mainstream discourse and that's more of maybe typical diet-culture sort of discourse, and then the idea that sugar is uniquely toxic and metabolic or whatever. I think that's more the dominant discourse in wellness culture and these wellness spaces where people are.

Karen Throsby: I think you're absolutely right.

Christy Harrison: Yeah, so it's interesting, but then the idea of addiction and the idea of this nostalgic sort of paleolithic past kind of unifies both of those cultures. It that's common. That shows up a lot I think in both diet and wellness culture. And for anyone listening who is kind of new to questioning diet and wellness culture and is like, well, isn't it bad we all be trying to get back there isn't sugar toxic? What would you say because you write that sugar is treated as being this indisputably bad thing for health despite a lot of actual uncertainty. And so I'd love to explore a bit what some of the uncertainties are here.

Karen Throsby: So one of the ways I've approached this whole project is to never say that sugar is good or bad, and it's very frustrating to some people. I think that I won't do that. And the reason I don't want to engage with that is that to place food in a binary like that where it's either good or bad, and we do it all the time with food, we oh, that's a healthy food, that's an unhealthy food, that's a good food. I ate some bad food today. Or that kind of diet-culture talk, that binary is so unhelpful because it only treats food according to its nutritional content. It's bad because it has calories or it's bad because it has a particular, stimulates the system in a particular way and it completely ignores the way that a food, yes could be calorific and if that's a concern or it could have an effect on the body, but it's also profoundly social.

And so when you think about sweet food and treats and how we use food to express sociality, to express love, to express care for people and we share food together, when you eat something, you often eating that with someone else. And the experience of the food is not just about consuming X and y nutrients, it's about being with others and food eating is inherently social. And so I think that good binary is very unhelpful. I think the other reason that I try and resist it is if I say sugar is not bad as I would want to say that I don't like the categorization of food as bad, that gets immediately read by others as me saying that sugar is good and that I am therefore somehow, and I get accused of this all the time, that I'm somehow in the pocket of the soft drinks industry or the sugar industry and I'm advocating for them because you are either against sugar or you are for sugar.

And so my position on this has always been what if we don't start there because if we start with me saying it's bad, the next question it has to be how do we stop people eating it, which is not a helpful question. Whereas if we don't start there, if we ask what does sugar mean to people when they eat it, then we can learn about its social significance. We can learn about the inequalities that are absolutely fundamental to all food consumption, including sugar. And so it opens up, what I'm trying to do with the book is to open up a new set of questions which are about food justice and managing inequalities and those kinds of questions. And I think saying that food is a food like sugar is good or bad acts as a block to those questions to discussions of inequality, for example. And so that's why I've kind of refused to engage with it. But it is quite interesting how it does infuriate. A lot of people I think who want me to begin by saying it's bad before we can move on to talk about inequalities. But my point is as soon as you say it's bad, you stop being able to have those conversations,

Christy Harrison: Right? Because then the conversation becomes, well, how can we stop poor people from eating it then?

Karen Throsby: Exactly. Not why are there so many poor people.

Christy Harrison: Right, exactly. I can relate to a lot of what you said, I think as a dietician who specializes in disordered eating and one aspect of my career, I wrote a book called anti-diet. I'm definitely not into diets and categorizing food as good and bad, but that does also a lot of bad faith interpretations I think have painted me as in the pocket of big sugar or big food or whatever. And I've never taken a penny from those industries and never will. Unfortunately recently in the us, I don't know if you've seen news about this, but there were a couple of anti-diet dieticians and other dieticians exposed in a Washington Post expose for taking money from soft drink industry for posts saying that aspartame isn't as terrible as it's being made out to be,

Karen Throsby: Which

Christy Harrison: Is true, and the science is really nuanced on that. And I think it's important to say that the panic headlines aren't correct, but unfortunately they were being paid by the soft drink industry to say that, which is super muddies the waters and is not helpful. And I'm sure they had their own reasons for doing those partnerships. It's all super complicated. But yeah, it's just so interesting how black and white and binary people's thinking is about this. And when I work with people on making peace with food and healing their relationship with all foods, including sugary foods, it's like I think it becomes such a different conversation where we start thinking about when sugar is forbidden or when sugar is out of reach or when you don't have enough food in the first place for reasons of dieting and disordered eating or reasons of food insecurity or both, it makes sugar, this forbidden fruit that tastes even sweeter and that you tend to feel out of control with or want to eat to a degree that is sort of like a rebound eating from the restriction. And when you take away that kind of push-pull dynamic, it can really find its place as just one food among many, and it has those associations with pleasure and sociality as you say, and also doesn't have to be such a big deal. But I think that's really radical for people who are used to thinking sugar is bad and I don't let it through my door, let alone touch my lips or whatever.

Karen Throsby: Yeah, and I think one of the kind of ways it intersects with inequalities is who's allowed to have treats, for example. It's just a really simple question. So one of the things that comes out in the book, and this is from self-help books and things like that, is often quite sort of middle class treats are seen as acceptable and in fact sort of middle class. And it is always mothers who are the target of these discussions. Middle class mothers who are seen buying their kids a treat are seen as being good mothers who aren't being too controlling and making their kids over anxious about food. Whereas poorer people who are giving their kids treats are seen as bad mothers because there's no entitlement there. And they're seen as having different kind of treats that don't carry the same status as sort of a confectionary chocolate bar and a creme brulee are treated very differently in terms of acceptability and then the questions about who's eating what. So it's very unevenly applied, and this is why I wanted to tie it to austerity because the same people who are being targeted as over consumers of public resources of welfare are being targeted as over consumers of low quality sugar and as somehow being incontinent, as being unable to control their consumption. They can't be trusted with it in the way that a middle class person can. And this comes through very strongly in the public health advice, for example.

Christy Harrison: Yeah, I'm curious to hear more about that. I'm coming from a US context where we have private healthcare, so we don't really have the discussion around who's costing the NHS money or whatever that you do there, but I think that discourse is still pretty common around the world in a lot of places, and it's really bound up so much with anti-fat bias, this idea that larger body people cost money and are drain on the healthcare system or whatever, and that we all have to do our part or something to lose weight and not take resources away from other people. It's just so stigmatizing and shaming, and I know people really struggle with that. I mean, weight loss is just not attainable in a long-term way for the vast majority of people. So it's inherently going to create this sense of failure among people who are told to do that. But yeah, I'm curious to dig in a little bit more into this relationship with anti-fat bias and how that shows up in the Rhetoric around sugar and healthcare in general.

Karen Throsby: Yeah, I mean the UK as you said, is a very particular context because we have national health service that in principle at least means that healthcare is free at the point of use for all. So we don't pay for healthcare except we pay through taxes and national insurance, and we do pay for it, but it's paid for differently and it's seen in the UK as a kind of national treasure. The NHS is very highly valued in population terms, and it's seen as something that is constantly under threat. I mean, it has been radically underfunded by consecutive governments.

And this creates tensions then, and particularly in the case of austerity for example, there was the idea that everybody has to be careful and look after yourself so that you don't create extra cost for other people. And fatness is always framed, I mean is always framed as being something that could be prevented, but it's a malleable issue and therefore people can and therefore should lose weight, which is assumed will make them healthier, which of course is also an assumption that raises a lot of questions. And so we have this Rhetoric, and it happened through covid actually where Covid intersected with discourses of fatness, which is this narrative of protect. The NHS was one of the slogans that the government was using during Covid Protect the NHS. And that's been used a lot in relation to fatness that it's seen as somehow costing money that could used for more innocent people.

Of course, we don't talk about that in the sense of lots of other illnesses and health issues. If you think about car accidents, for example, which are also preventable, a skiing accidents, but there is a focus on fatness where people are seen as undeserving consumers of public resources again, and in the UK that's a very strong narrative. You will be lectured about it by doctors and its people will be bullied because of this, get very poor treatment often in healthcare settings because their fat won't have entitlement to treatments because of their size. So there are weight thresholds on access to some surgeries, for example. And so then sugar just tapped into this perfectly because the attack on sugar makes it seem so simple to manage, just give up sugar, it's a single nutrient, and you give that up and it was really heavily weighted as the solution to the problem and to protecting the NHS. And so what that does is generate a great deal of blame on people who are fat in ways that already isolate and stigmatize a group who are isolated and stigmatized. And it just kind of intensified when you bring it down to a single nutrient. If only you stopped eating sugar, then you just intensify that blame in ways that are just, I mean, incredibly reductive and actually very abusive. I think.

Christy Harrison: I agree, and I think you make the point in the book that sugar is treated as the single nutrient sort of source of fatness and poor health and all of these things, and yet it never really functions in a single nutrient sort of way in practice that it comes with other nutrients and other foods. And we're not just sitting here eating handfuls of granulated sugar. It's like we're eating food and engaging in pleasurable activities and connecting over food, and then some food happens to have sugar. But then you also point out that there's this discourse around hidden sugar lurking everywhere and that you have to learn to be a sugar detective to root it out and make sure you don't have hidden sugar in your food. But it's just so interesting that there's that singular focus when we don't consume things in isolation like that.

Karen Throsby: No, I mean sugar's one of a very few things that we just really don't eat it. I mean, you might think of some sweets candy that is probably mostly sugar, but we really don't eat sugar on its own. And so it's in foods which creates this. So if the task sort from a policy point of view, the task has been how can we get people to eat less sugar? And often how can we get those people to eat less sugar is a very common inflection of that. And then what follows is an education where people are taught how to find sugar in their diet and cut it out. And this comes particularly in relation to, as you said, to sugar that is seen as hidden. So actually a lot of the anti-sugar self-help books and things aren't really focusing on obviously sugary foods, cakes, biscuits and things like that.

Instead they focus, and certainly the newspaper coverage focuses on foods that you might not expect to contain sugar, but where sugar is present. So things like pre-made pasta sauces and things like that, what savory foods, tin soups, all those kinds of foods. And then foods that claim to be so-called healthy. So things like cereal bars and things like that. So where you might not necessarily expect to find sugar, and then people are kind of educated through these newspaper articles and books on how to dig it out. And so you're supposed to then become hypervigilant in terms of reading labels. So there's an awful lot of instruction on how to read a label, how to translate a label, what the different names for sugar, how to calculate sugar is a really big thing, and then what your allowance would be. And so there's a lot of these newspaper articles where I called them the mortified mother stories where a woman is always a woman would keep her food diary for say for herself or her kids for her partner, and then the nutritionist comes in and sort of analyzes it and always kind of finds them wanting in terms of, oh, you are having too much sugar here, too much hidden sugar here.

And then the women are kind of educated in how to identify where the sugar is and then rooted out. And this is often done through, for example, not using pre-made products. So instead these women are encouraged to, instead of having cereal for their kids, they'll encourage them to make porridge on a stove top or to home bake things. So of course what you've got here is a duplication of is it an increase in work for women because they're having to monitor the sugar, calculate to keep records, keep diaries, constantly read labels, and then do the work of giving up sugar, which is replacing the food. And none of this is recognized in any of this kind of pedagogic material as being work. It's simply the work of being a mother. It's what a mother would do, it's what a woman would do. And so the whole industry of giving up sugar is actually premised on the unrecognized work of women. And this rooting out of sugar as hidden is not an innocent pastime that falls to everyone. It's actually very unevenly weighted in terms of falling onto women to find the sugar and dig it out on everyone else's behalf

Christy Harrison: And then make alternatives to it at great cost to them too.

Karen Throsby: Yes,

Christy Harrison: Which I mean it all strikes me as you were talking about that I'm like, oof, what a time suck. And ultimately to me feels like a waste of time having gone through it myself, having been trained as a dietician where 12 years ago, 15 years ago, whatever, I could have been that dietician going into the house and telling people where the hidden sugar was, that's what we were trained to do. But then also as someone who had disordered eating myself for many years and was super obsessive about what I ate and focused on reading labels and spending so much time before going to a restaurant, scouring the menu and all of that stuff, it's just like how much time that sucks away from things that we actually bring us joy and connection and fulfillment and all of that stuff.

Karen Throsby: And there's actually quite an interesting tension here that comes out again in these stories, these food diary stories, which is that this encouragement to become really quite obsessive about monitoring sugar and leaching it out your diet, but at the same time, there's a whole series of warnings that you mustn't become obsessed with food unhealthy,

And particularly in relation to children and particularly in relation to daughters, you get this message. So there was a case of one of the stories I talk about in the book, which is a food diary story, and one of the women whose family they look at actually the diet has got almost no added sugar in it, and they eat a lot of fresh fruit and vegetables and the dietician, the nutritionist is very approving, but then she kind of says, ah, but you don't want your daughter to become obsessed and develop disordered eating, so you need to make sure that there's treats, there's sugary treats in there. And so it's the dilemma of womanhood really, that you have to focus on your body, but you shouldn't be too focused on your body and this is being reproduced in relation to these foods. So in a sense, the women are being taught to make this work appear natural and effortless. So it's not an obsession, it's not kind of laborious, it's just something that happens and you do it and only good things come from it, and therefore it doesn't even feel like work.

Christy Harrison: Wow. Yeah, I mean it also strikes me how much that is co-opting of the messages of eating disorder prevention and anti-D diet work because those messages go out there and would seem to run counter to sugar obsession and rooting out sugar in a hyperfocus on sugar, other nutrients deemed bad or foods whatever deemed bad. But it just sort of gets folded into this larger diet and wellness culture message where it's like, okay, now here's this other side to the razor's edge. You're supposed to walk and you don't want to fall over here on this side bad sort of missing the point of what a peaceful relationship with food actually looks like. And we don't have to walk this razor's edge.

Karen Throsby: And I think that what you've said about wellness and the wellness industry is really interesting there because one of the most common features of the self-help books that are supposed to teach you how to give up sugar is that they begin by saying, this is not a diet, which of course is straight out of the diet-culture slash wellness playbook.

And so mainstream diet industry uses that. Slimming clubs, commercial diet organizations use that narrative as well. It's not a diet, it's a way of life. It's that kind of talk. And then the anti-sugar people are saying that this is not a diet, this is a revolution, this is an investment in myself, this is all of these things that it's not a diet, it's not something as what they're framing as kind of trivial attempts to lose a bit of weight. It's being turned into something more serious. But it is at the same time completely mirroring the language of wellness culture, which is kind of very masterfully done. This kind of distanced itself from diet-culture whilst reproducing it

Christy Harrison: And while making it seem so much more important, and this is

The language of revolution, it just makes my skin crawl that they're those terms. But I do think there are people out there who feel like, well, yeah, there probably are some people listening who are like, but that sugar is uniquely bad and there is this thing about it that we just really have to take it out of our diets and do what we have to do. And it's not as trivial as a diet and blah, blah, blah. And the uncertainty around the, so-called badness of sugar, and I think too, the Scientific uncertainty is really worth exploring more personally. I've done deep dives into the Scientific literature on this because I get so many questions from people about sugar. Is it really okay to eat sugar? How much am I eating too much? I'm in this sort of honeymoon phase with Intuitive Eating where I'm eating all the foods that were previously forbidden.

I'm eating nothing but sweets. Is this okay? Am I harming my health? Blah, blah, blah. And I totally get it. I've been there too. And I feel like it's scary at first to come back from a place of totally restricting sugar, and you do often swing to the other side of the pendulum. And when I've delved into the Scientific literature, it's so much more squishy and there's so many other explanations for why sugar is associated really mostly just association. It's not causation. It's like people in the highest quintile of sugar consumption have X times the risk of heart disease than people in the lowest quintile or whatever. But then when you look at what people are actually eating in those quintiles and you're like, is that life where you're eating this much or you're eating that much sugar and they're not controlling for socioeconomic status, they're not controlling for all these things that could make that difference.

They're not controlling for disordered eating either, right? Because when you're in the highest quintile of sugar and consumption, it's possible Binge eating disorder is a part of that. And nobody, for some people, not for everyone, of course, but nobody's talking about that or controlling for that and the health outcomes you might have from bingeing eating disorder or from living in poverty and the stress and discrimination and lack of access to care and all the rest that goes along with that is probably going to account for much if not all of those excess risks that we see in the people in the highest quintile of sugar consumption versus the people in the lowest quintile who by the way, are not eating no sugar too. I always point that out to people. It's like they're kind of eating a decent amount of sugar, like sugar throughout the day perhaps, or sugar desserts and sweetss and stuff.

Karen Throsby: It's

Christy Harrison: Not nothing. So yeah, it's just interesting to me sort of the uncertainties that are there and yet just get totally swept under the rug when it comes to the discourse and this sort of inflated Rhetoric around, it's a revolution, it's a lifestyle. This is so much more than just a diet.

Karen Throsby: And I think it's important to note that about who gets the kind of social benefit for giving up sugar, that it's become a very middle class way of gaining status to be sugar free, to cut out sugar. It's a way, but actually the people who are able to give up sugar in that way and make those claims and gain capitalize on that are also the most privileged, so that those who are advocating giving up sugar are the ones sort of best positioned to capitalize on that and others who are living much more difficult lives. Not that someone who's middle class may also be living a difficult life, but very constrained, straightened lives, people who are very limited on resources, who have no money, nothing to fall back on, lots of stress, often very difficult working conditions, very low pay, poor housing, poor healthcare. To then say that giving up sugar is the important thing is actually quite insulting when there are many, many problems, and there's lots of sociological research on this about how food decisions are made. For example, it may be that if you are living in very straightened circumstances, you are investing in health in the present because that's all you can do, which is, for example, to make sure that your kids are not hungry, which is a form of health to not be hungry. And that may be giving them whatever they will eat that's affordable.

Obviously children, it takes a long time for them to learn to eat something new and different. And if you haven't got any money, you haven't got time, the space for children to waste food. So you would give them what they're going to eat and also just treats, just sometimes. So there's a story in the book that I took from a book by Pryor Fielding singer, a US sociologist, and she tells a story of a woman called Aya who takes his very, really struggling for money. She's barely got $10 to put petrol in the car, and she takes her daughter to a coffee shop and they buy two of those big kind of coffee shakes with all the cream and the toppings and things, and she spends $10 on this. And what Fielding Sing says is the sort of dominant narrative is here's a woman who's really poor, who is wasting money, can't be trusted. But actually when the author Fielding Singh asks her why she bought the shake, she says that just once, she wanted to be able to say yes to her daughter because she always has to say no. And I think you can't fit that into any narrative that begins with sugar is bad, that there's so much else there about what that means to her as a mother to the child, to what it is to live in poverty. And so that's why I'm kind of just very resistant to this narrative that sugar is bad because it's a narrative of privilege To be able to give up sugar is an act of privilege.

Christy Harrison: Yeah, so true. I think too, the narrative about sugar being addictive is so interesting because it dovetails with demonization or stigma against people who are addicted in general. And again, it's like who tends to fall prey to addiction more frequently? It's often people in dire circumstances where that's a coping mechanism that's kind of readily available. And again, it's like sweeping these discussions of privilege kind of under the rug and focusing on just this supposed addictive nature of sugar and that people need to use willpower to overcome it or whatever. And I'm curious what you found in your reading of the research on so-called sugar addiction and how you would nuance that.

Karen Throsby: I mean, the literature on sugar addiction is very, there's a couple of papers that get cited repeatedly that were experiments with rodents where the rodents were given. Some of them are given a sort of liquid cocaine and then are given sugar, and if they choose sugar that's red as sugar is more addictive than cocaine. And then actually when you read the papers, the claims that can be made for the research is much more nuanced. For example, it appears that they may be seeking sugar to relieve some of the symptoms that heroin can be quite aggravating, and also people aren't rodents and you have a social relationship with these foods. And so what I found in the literature was that there was a chain of studies that get cited again and again and again that are used to make the case A, that sugar is addictive and then that sugar is more addictive than cocaine say that it's the most addictive thing.

But what's interesting for me is then a lot of these authors who are writing about sugar as addictive also are pretty casual about the fact that the assumption that you can give it up and they often use their own bodies as an example, that I was addicted to sugar and I gave it up, which is actually, if you're saying it's addictive, that's quite a self-aggrandizing statement. If it can just be given up quickly, what does that mean to say it's addictive if you can just stop. It's also very gendered, actually the language of addiction. And so women are often talked about as being much more likely to be addicted to sugar and finding it much harder to give up sugar, which I've always sort of found because that taps into an idea of women as being hyper vulnerable to sugar, a bit like children. So it infantilizes women.

So the idea that it's addictive, I think it blurs lots of different ideas of addiction because people would say things in articles like, oh, sugar's addictive, because once I've opened a pack of biscuits, I can't stop eating them. And is that addiction, what does that mean to claim that that's addiction? How would that compare to the Substack that you can't stop thinking about that. You break the law to go and get the resources to buy it versus not being able to stop eating a packet of sweets until you get to the bottom. And so clearly something is happening there in terms of it being very moorish and hard to stop eating it. But the language of addiction is a very kind of big stick, I think to wield that raises the sense of emergency around sugar. And that's how it's used. It's used, the claim that it's addictive is used to make sugar a more urgent problem by basically aligning it with tobacco.

I mean, that's the other way that it connects with addiction. So the tobacco industry is very well known for having a kind of playbook for tackling attempts to legislate smoking, to ban smoking, and there's a playbook of ways of co-opting scientists and so on. And a lot of the people writing about sugar say that it's, and there are some similarities that sugar is like tobacco because the sugar industry is behaving in the same way as the tobacco industry in terms of its co-opting scientists, the way it's advertising, the way it's creating uncertainty about what we know about sugar. These are all ways of tackling attempts to regulate. And so it's another parallel that gets drawn that sediments, this idea that it's addictive in the same way that we would accept tobacco is or illicit drugs.

Christy Harrison: So interesting. And I mean obviously that is problematic in industry co-opting scientists and trying to avoid regulation. And I think that to me, all this conversation about addiction misses such an important piece, which is the deprivation part of it. And when you look at those animal studies, I can't remember if it's the one with cocaine or not, but a lot of them, the rodent studies, the rodents are deprived of food for a long time, and then they seek out sugar, and it's like, well, maybe they're hungry and they don't feel like doing Coke right now. They feel like eating. That's one approach that, or one reading of it that I think doesn't really get discussed outside of eating disorder and fat studies kind of circles and the deprivation inherent in people feeling like they can't stop eating before they get to the bottom of the bag or whatever. It's so clear from my personal experience and working with clients and in the literature as well, that when people are well fed and eating intuitively and following to whatever extent possible eating when they're hungry and when they have access to enough food to be able to do that, people don't tend to have that experience that they tend to be able to regulate more with those kinds of foods than they would otherwise when they're deprived.

Karen Throsby: Yeah, yeah. And I mean, think in terms of when we're talking about industry, I think one of the frustrating things, like I said earlier, that by refusing to say that sugar is bad, I'm often seen as defending industry or I'm asked if I'm funded by industry. And I think in the book, I think it's very clear that, I mean, I find these industries very problematic. Their job is to make money for shareholders, and they do it incredibly well, and they are using every weapon in the arsenal in order to maintain their reputation and so on. But they're also, a lot of these companies are environmentally devastating. They have terrible kind of labor relations. There's lots of reasons why we should be concerned about these companies, and I'm certainly not a friend of these companies, and I'm certainly not funded by them. And I think anybody who really kind of read the book would know that. But I think it is important to look at the tricks that they are using to market these products, the language of health, the language of wellness, the language of, so protein is the latest one. There's protein, everything, protein, Mars Bars, protein, everything, protein. And these are all strategies. And I think it is good to be aware of some of the limitations of the claims. I don't think to say that is incompatible with my skepticism about the attack on sugar.

Christy Harrison: Right. Well, and I mean, I often think there are two sides of the same coin. The food industry is in many ways the same as the diet food industry. It's the same companies that have the diet food brands and diet, food and deprivation can help drive that sense of out of control and feeling like you have to have that you, you're going to eat it all. I don't really like the term overeating. I don't tend to use that. I think it's stigmatizing, but people feel like they're overeating or they having a rebound basically with these foods that were off limits. And those large food companies are one in the same as the diet companies that are sort of creating this situation that sets people up to do that. And whether that's intentional or not, who knows. I don't know if people in those companies understand that relationship. I mean, some might. I think it is really problematic in that sense too, that diet-culture and diet food companies are contributing to this situation that then leads people to feel like they're drawn to foods like sugar and sweets and all the other stuff.

Karen Throsby: Yeah, exactly. And in the UK we have a sugar tax which have been applied particularly to soft drinks. But what's kind of interesting about that is so lots of companies have reduced the sugar content of their drinks in order to bring it below the threshold for the sugar tax. But actually what it's led to is what the push towards reformulation has led to is a proliferation of products. So a soft drink that you might still have, they might still be selling the original version, the full sugar version, but then there'll be a diet version as well, or a low sugar version. And so actually we've seen this multiplication of products, so marketing them as sugar free is a kind of clever marketing ploy or as healthy or whatever language, but often the original products are also still available. So I mean, they are capitalizing on it. They're very shrewd understanding of how this attack on sugar is working.

Christy Harrison: They're really playing both sides and trying to skirt out of the regulations by offering this new line, but then also keep the core product that I'm sure still sells well. Yeah, it's very clever.

Karen Throsby: Exactly.

Christy Harrison: So this podcast is called Rethinking Wellness, and I've been asking all my guests, how are you rethinking or how have you rethought wellness in light of your work?

Karen Throsby: That's a really interesting question. I mean, I think I was very conscious when I started this project that I didn't want to start looking at my own sugar consumption because I was reading so much about it and this constant urging to be reading labels and limiting my sugar. So as a result throughout, I worked on the project for about five years in total, and I never actually gave up sugar at any point. I never tried giving up sugar entirely. I don't read labels, and I never really, really got into that. I am very closely allied with what I would think of as critical fat studies in my academic life and think very critically about these things. And so I try not to, and this precedes the sugar project, as I try not to weigh myself, I try not to get too caught up. I think it's hard never to get caught up in your body size and appearance.

And I've tried to maintain that, I think. And in a sense, the critique, particularly around the language of wellness and so on, has helped me, I think has pushed me towards thinking about how I'm investing in my body. So I do a lot of endurance sport. I'm a long distance swimmer, and so I've been trying to focus on performance rather than appearance. So am I doing the distance I want to do? Am I doing the times I want to do? And to think in terms of wellness in that sense, I'm 55, I'm a menopause. I'm just about at the end of going through menopause. That has huge effects on the body. The way you metabolize food, the condition of your body changes enormously. And so I'm been trying to focus on that and managing that rather than thinking in terms of weight. And I think with the sugar project, I had to do that quite deliberately because I was reading about fatness all the time and this anti-fat.

And then I think when you read a lot of anti-fat talk, even when me, you have a very critical view of it, it is very hard to resist. And you do find yourself in those moments thinking, oh yeah, I'm a bit, I should probably do something about that. And I think it's a kind of warning as well that it sneaks in there. Even if you are alert to it, you start having those thoughts. And so I actually, I guess my investment in wellness, if you was my rethinking of it, was to kind of try and actively resist those feelings of, oh, actually yes, while I'm at it, I should lose a bit of weight.

Christy Harrison: That's so interesting. And I definitely identify with that. I had a baby a year and a half ago, and my body changed a lot as a result of that. And it's even with years and years of anti-diet, eating disorder recovery, and then anti-diet work as a dietician and all that stuff. It's still, the body image stuff still comes up sometimes. And that's something to navigate. I think about, I dunno if you've read Abigail Sge and

Karen Throsby: Frederick,

Christy Harrison: Yeah, what's wrong with fat? And their research on the frames, anti-fat frames in newspaper articles. So for anyone who hasn't heard of this, I'll link to the study in the show notes or there's a couple of studies, but they showed people these different constructed articles that they had different framings. One was like, obesity is bad and it's a personal responsibility and people need to lose weight for their health and blah, blah, blah. And then another one was a health at every size message with messages about body positivity, et cetera. And then they tried one that was like, obesity is bad, but don't stigmatize fat people. And it adding this anti-stigma message and found that even when the anti-stigma message was added, merely reading that one, framing fat as bad, had some negative impacts on people's views of larger body people and willingness to discriminate against 'em.

Karen Throsby: Yes. And mean, I think for me it's about acknowledging that you can never step outside of the social. I mean, it's a very kind of sociologist's point, but can I can critique the social world in the world that I encounter and I can think critically about it, but you can never step outside of it. And so I think one of the things that I see in critical fat studies or health at every size communities is actually, and when I talk about this with students, there's often people will express a lot of guilt that they're not able to quite relinquish the desire to be thinner. And then it's just more guilt. And I think it's really important to acknowledge that we cannot step outside of it and it's there and you can take all kinds of steps to try and mitigate against it, but to have those thoughts that are actually, wouldn't it be great if I lost some weight? It's not a failure. It's not another source of guilt to be dealing with because that's how the social world works. We're in it. You can't escape entirely from it. You can only engage critically with it, I think, and then try and enact change.

Christy Harrison: It's a really helpful message and I think a good note to end on for this main episode. So thank you so much for everything you shared. Can you tell people where they can find your book, the title and how they can learn more about you?

Karen Throsby: Yes. The book is called Sugar Rush: Science, Politics and the Demonisation of Fatness. It's published by Manchester University Press earlier this year. It's available online through the Manchester University Press website. Would be a good place to go to purchase the book.

Christy Harrison: Amazing. We'll put a link to that in the show notes as well so people can find it.

Karen Throsby: Great. Thank you.

Christy Harrison: Thank you so much, Karen. It's a pleasure talking with you. And if you have a few minutes, I'd love to have you stick around for the bonus episode.

Karen Throsby: Absolutely. Thank you very much for having me on today.

Christy Harrison: So that is our show. Thanks so much to our amazing guest for being here and to you for tuning in. If you've enjoyed this conversation, I'd be so grateful If you could take a moment to subscribe, rate, and review the podcast on Apple Podcast, Spotify, or wherever you're listening. You can also support the show by becoming a paid subscriber for just a few bucks a month with a paid subscription. You unlock great perks like bonus episodes, subscriber-only Q&As, early access to regular episodes, and much more. Sign up now at rethinkingwellness.substack.com. That's rethinkingwellness.substack.com. Got burning questions about wellness trends, diet fads, or anything else we cover on this show? Send them my way at christyharrison.com/wellnessquestions for a chance to have them answered in the Rethinking Wellness newsletter or on a future podcast episode.

This episode was brought to you by my new book, The Wellness Trap: Break Free from Diet Culture, Disinformation, and Dubious Diagnoses and Find Your True Well-Being, which is now available wherever books are sold. Just go to christyharrison.com/thewellnesstrap to learn more and buy the book or just go into your favorite local bookstore and ask for it there. If you're looking to heal your relationship with food and break free from diet and wellness culture, I'd love for you to check out my online course, Intuitive Eating Fundamentals. Learn more and enroll now at christyharrison.com/course. That's christyharrison.com/course.

Rethinking Wellness is executive produced and hosted by me, Christy Harrison. Mike Lalonde is our audio editor and sound engineer and administrative support is provided by Julianne Wotasik and her team at A-Team Virtual. Our album Art is by Tara Jacoby, and our theme song is written and performed by Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs. Thanks again for listening. Take care.

Share this post